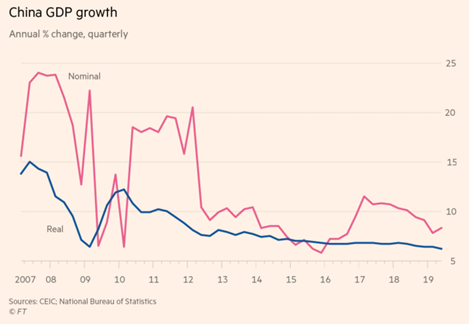

China’s economy grew 6.2% year-on-year in the second quarter of 2019, the slowest pace in almost 3 decades. The new growth figure continues a long-term trend of decelerating Chinese growth:

More recent data on industrial production and retail sales tell a similarly grim tale.[1]

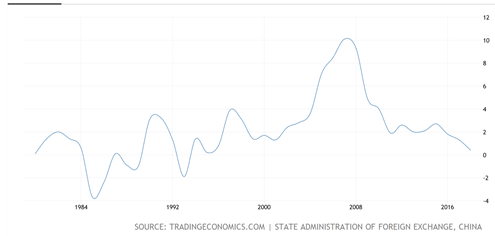

Explanations for this slowdown (whose beginning predates the fairly recent US-China trade war) often cite declining export growth. China’s trade surplus inflated rapidly after it joined the WTO in 2001, reaching almost 10% of GDP in 2007 before falling to 0.4% of GDP in 2018:[2]

China Current Account Surplus (Percent of GDP)[3]

Some analysts argue that China’s recent growth slowdown has been driven by this flatlining of export-related economic activity.

But over the past 40 years, net exports have only contributed about 2 percentage points annually to China’s GDP, which in itself has grown at an annual rate of around 10% over the same period. Moreover, this level of growth has previously maintained even during periods in which China’s trade surplus was close to 0% of GDP. This means that even the near complete obliteration of China’s current account surplus in recent years can only explain a fraction of slowdown from its historic growth rate to the current 6.2% year-on-year expansion.

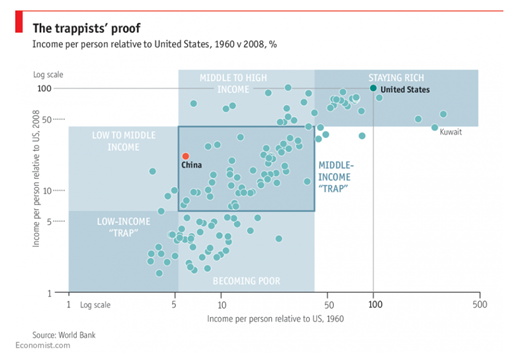

Other analysts argue that China is falling victim to the ‘middle income trap’, where rising wages lead to a loss of a key competitive advantage (cheap labour) in international trade, making the country a less attractive investment destination and thus hampering growth. Again, however, this explanation has shortcomings – in general, there is limited evidence for the notion of a ‘middle income trap’, with data revealing few examples of countries that have stagnated in the middle-income phase of development:

Indeed, though countries lose the competitive advantages afforded by cheap labour as their economies grow, they simultaneously realise new means of adding value as they develop a healthier, more skilled workforce, improved national infrastructure, better-functioning institutions and greater access to financial markets. In China’s case, a focus on labour intensive manufacturing facilitated by an abundant supply of cheap labour has been replaced with an emphasis on the production of high quality, R&D-heavy using less labour-intensive but more skill-dependent manufacturing processes:

The middle income trap hypothesis therefore provides a poor explanation for China’s current growth slowdown.

Pritchert and Summers (2012) have suggested that China’s slowdown is a case of regression to the mean: they argue that there are few persistent, country-specific factors that can consistently boost or reduce any country’s growth over large stretches of time, meaning that in the very long term it is unusual for a country’s GDP growth to depart markedly from the global mean. While China has been one of a handful of exceptions to this trend over the past few decades, rare exceptions are expected given that regression to the mean only operates probabilistically. As such, there is no reason to use China’s historical growth rate of ~10% per annum as a standard against which expectations for current growth should be derived – according to Pritchert and Summers (2012), there simply is not enough consistency in country growth rates across decades for this to be a valid basis on which to set growth rate of 6.2% per annum, which is much closer to the global mean.

However, in spite of its solid statistical grounding, this approach leaves unanswered questions about China’s growth slowdown. The fact that China’s growth slowdown may not be unusual from a statistical point of view does not tell us why it has happened and what makes today’s China different from the 10%-annual-growth China of the past.

The most compelling explanation, in my opinion, is the one most aptly presented by Nicholas Lardy in his recently published book ‘The State Strikes Back’. To summarise his argument:

- China’s post-1978 super-rapid growth was supported by ongoing pro-market reforms that progressively expanded the role of the private sector in the economy while reducing state control.

- Since around 2012, the Chinese government has reversed this pro-market trajectory with policies designed to reallocate resources to state-controlled enterprises at the expense of private business.

- The expanding role of the state in the economy has dragged down growth, largely because state-owned enterprises operate less efficiently than their private counterparts.

Let’s explore each of these points in more detail:

China’s post-1978 super-rapid growth was supported by ongoing pro-market reforms

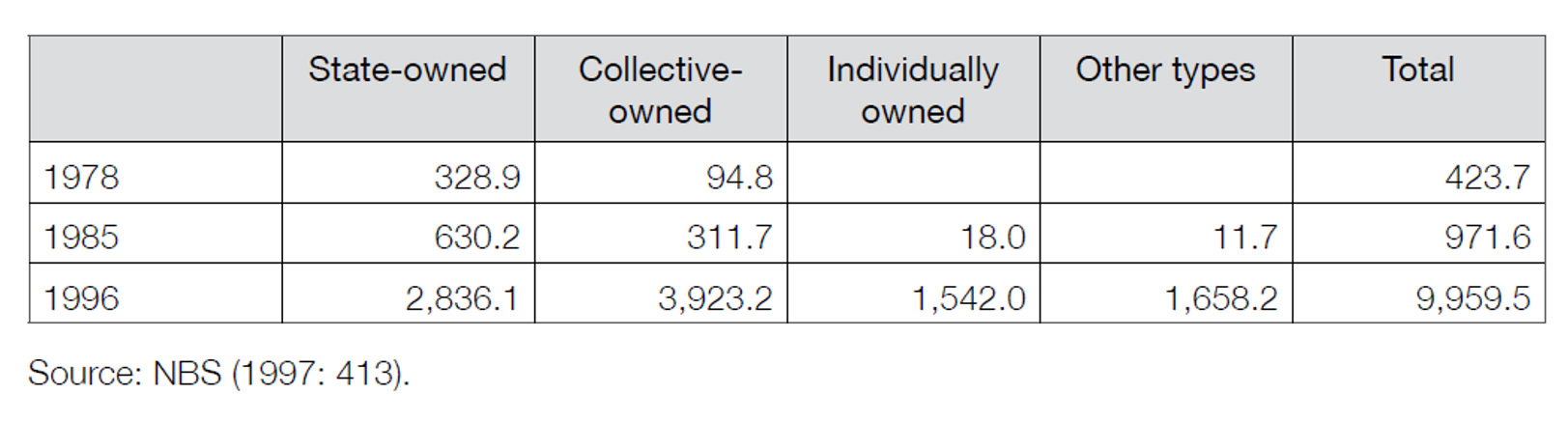

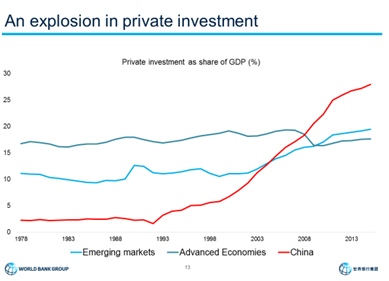

Deng Xiaoping officially began China’s policy of reform and opening up in 1978, a massive campaign of market liberalisation that saw the expansion of private property rights and private business ownership, elimination of numerous price controls, reductions or removal of inter-province and international tariffs on goods and services, and the withdrawal of various state-run schemes in which housing, schooling and medical care were allocated to millions of Chinese citizens by the Government. Since then, the country has experienced a massive surge in private economic activity.

For example, the table below shows that the proportion of industrial output attributable to non-state-owned firms surged drastically following the reform processes that began in 1978.

Gross Industrial Output Value by ownership

Data on the sources of fixed-asset investment paint a similar picture:

Indeed, while pre-1978 China’s economy contained no private enterprises, today around 60% of Gross Domestic Product is attributable to private sector wealth creation.[4]

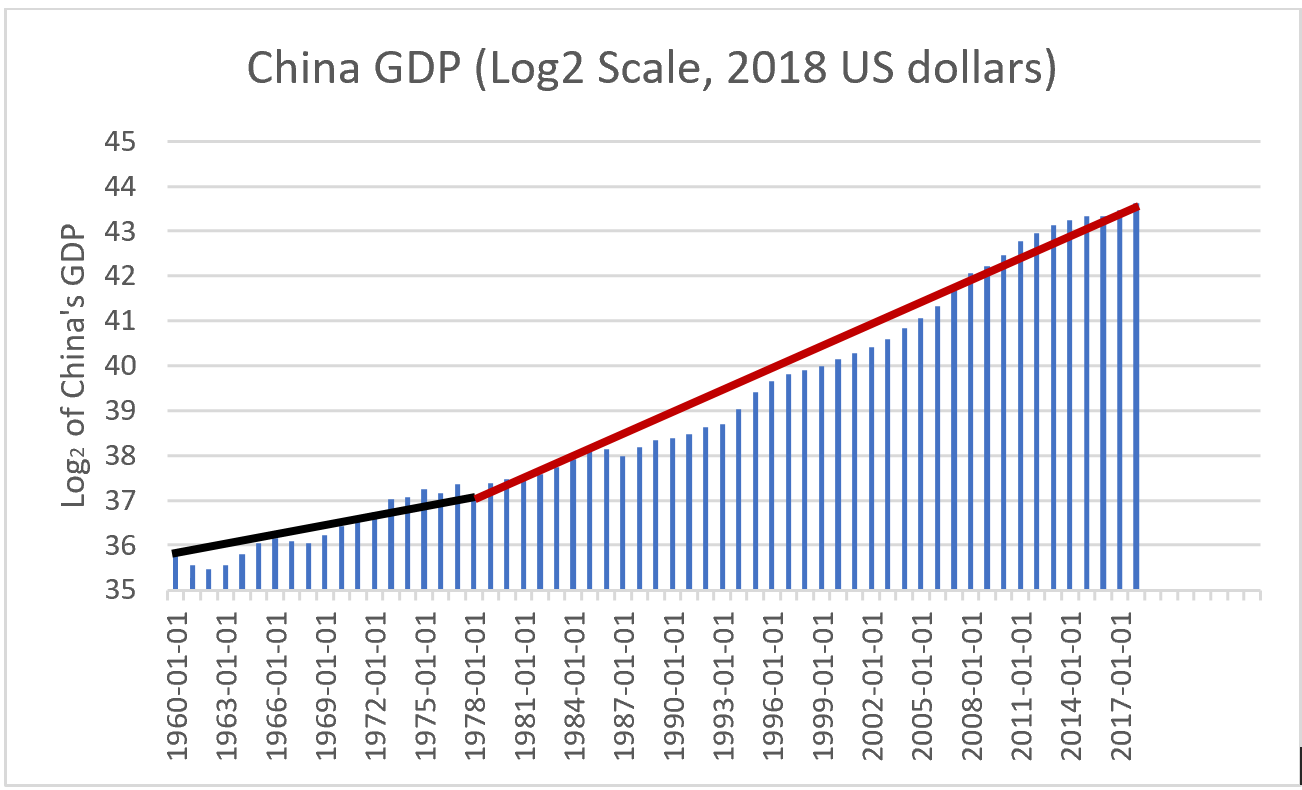

The effects of China’s growing private sector can be seen in its GDP growth over the past 70 years, which is presented below on a log2 scale – the use of this scale means that an increase of 1 on the Y-axis indicates a doubling of GDP, meaning that the gradient of the linear trend on the graph tells us how quickly China’s economy was doubling over a given period.

Between 1960 and 1978 (black line on the chart), we see an increase of about 1 on the Y-Axis, meaning China’s GDP doubled once over this period. But between 1978 and 2018 (red line on the chart), we see an increase of more than 6 on the Y-Axis, meaning that China’s GDP doubled 6 times over this period. So, we go from doubling on average every ~16 years pre-1978 to doubling at a rate of almost once every 6 years post-1978. This indicates that China’s opening of its economy and market liberalisation appear to have made a strongly positive contribution to its growth in the past.

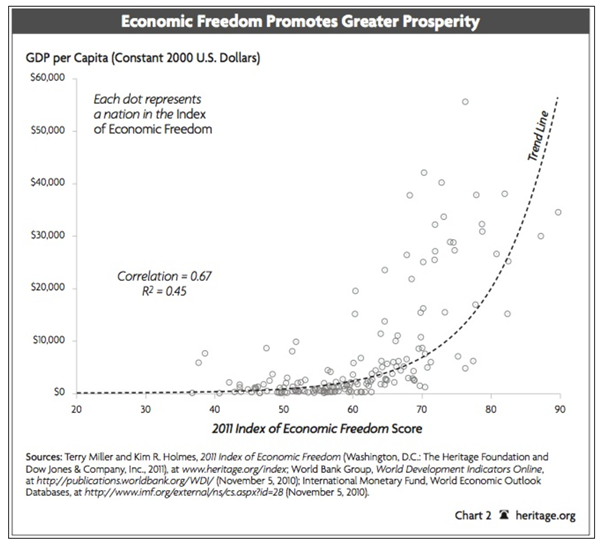

This is consistent with the well-evidenced finding that, in general, economic liberalisation tends to be associated with high GDP[5]:

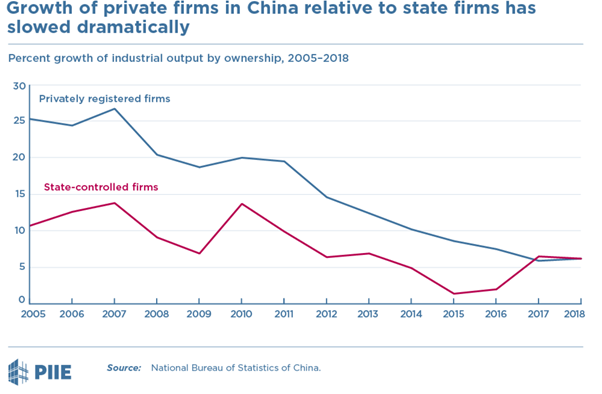

Since around 2012, the Chinese government has reversed its pro-market trajectory

A number of data sources attest to a growing role of the state in the Chinese economy over the past decade. For example, although state-owned enterprises comprised a diminishing portion of industrial economic activity from 2000 to 2009[6]:

This trend is now reversing[7]:

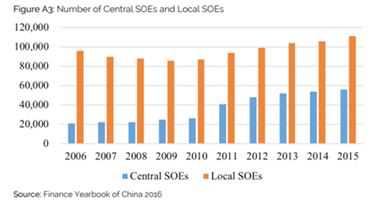

And the number of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) is increasing across the whole economy[8]:

The decline in their contribution to the nation’s fixed access investment is also beginning to reverse[9]:

This new-found advantage of SOEs has been driven to a large extent by the fact that they have been finding it increasingly easy to access loans relative to their private counterparts[10]:

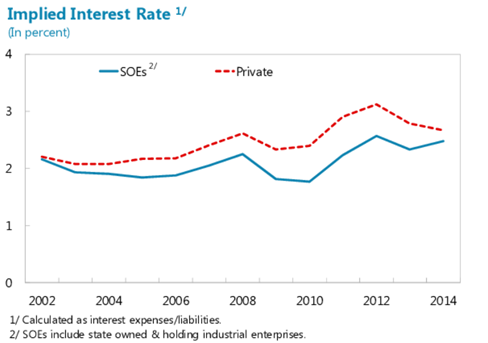

And pay lower rates of interest on these loans[11]:

Thus, in a reversal of the trend that characterised China’s economic development from 1978 until around 2009, SOEs are achieving growing prominence in the country’s economy at the expense of private sector growth.

In itself, this might not necessarily a bad thing – in a well-functioning economy, more competently managed companies should generate more profit, enabling them to receive more financing from investors and lenders, acquire more assets and hire more workers. This process naturally ensures that a country’s limited resources are increasingly placed under the control of companies and individuals that are likely to utilise them more efficiently. It could be, then, that the past ~decade of growth in SOEs is simply due to the fact that they are managed more effectively than private firms.

However, there is strong evidence that this is not the case – rather, the current phase of SOE growth is the product of a government-backed policy to support SOEs at the expense of private firms, primarily, but not exclusively, by encouraging state-owned banks to lend preferentially to SOEs.

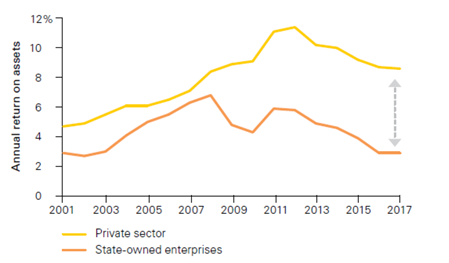

Indeed, data on return-on-assets generated by private firms and SOEs strongly suggest that the former operate more efficiently. Return-on-assets is calculated as a company’s annual profit as a proportion of the value of the assets that it uses to generate that profit, meaning that companies that make more efficient use of their assets should have a higher ROI. China’s private companies have far higher ROIs than their SOE counterparts, and this divergence has increased since around the time when bank lending to SOEs witnessed an upwards surge[12].

Moreover, not only has the average ROI among SOEs decreased over this period, but the number of loss-making SOEs and the magnitude of their losses has increased. These losses are disproportionately incurred by relatively more indebted SOEs – so in contrast to the situation in a well-functioning economy, where credit would generally be denied to poorly performing companies, it appears that those SOEs that are incapable of supporting themselves by generating a profit are saved from collapse by easy access to cheap credit, largely provided as a result of government pressure on state-owned banks.[13]

This indicates that SOEs are increased sheltered from market pressures by their preferential access to credit (among other pro-SOE state policies), which allows inefficient, unprofitable businesses that would normally be pushed to bankruptcy by market discipline to survive while hoarding labour and resources that would otherwise be utilised by more efficient firms.

Indeed, research by Lunqvist et al. (2015) indicates that SOEs are not well incentivised to maximise efficiency. Lundqvist et al.’s (2015) analysis of data on the allocation of financial resources to SOE subsidiaries by parent companies found that subsidiaries with fewer good investment opportunities are allocated more capital by the parent SOE than subsidiaries with good investment opportunities available. This indicates that rather than being incentivised to maximise profits, SOE executives are incentivised to avoid the lay-offs and bankruptcies that would occur if access to capital were to be restricted for poorly performing subsidiaries.

In normal market conditions this would be unsustainable, because lenders would be unwilling to continue supplying capital to firms that appear doomed to imminent failure. In China, however, state-owned banks face pressure from the government to continue lending to SOEs; they also know that the state would be unlikely to allow large SOEs to fail but would be less concerned about private insolvencies, creating a situation in which SOEs are (correctly) regarded as lower credit risks in spite of their lower creditworthiness. These distorted incentives on lenders ensure that credit continues to be inappropriately allocated to SOEs at the expense of more efficient private firms.

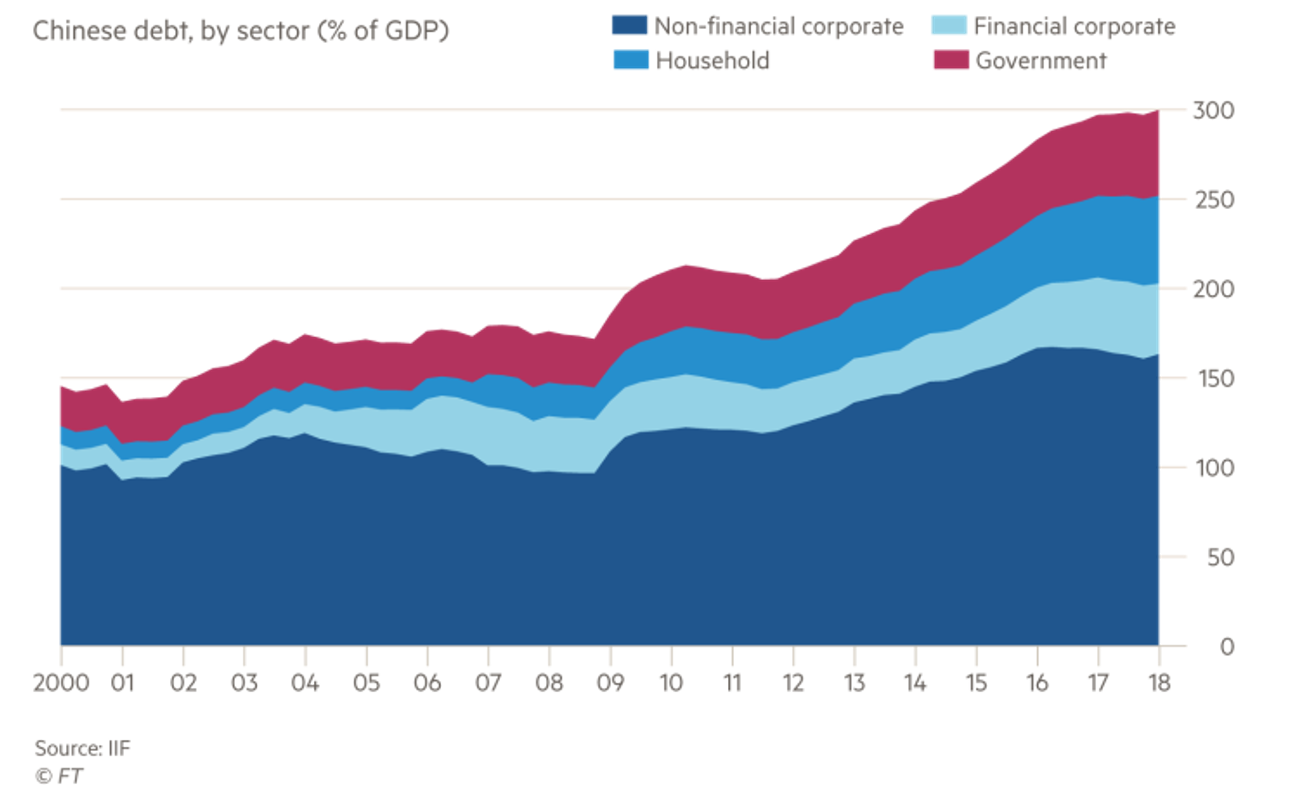

One way in which private firms have attempted to circumvent their difficulties in accessing credit has been to seek loans outside of traditional financial markets. For example, loans issued by the shadow banking sector, in which much more loosely regulated lenders operate, have surged over the past decade. This market almost exclusively serves the private sector and lend at higher rates of interest to standard banks, placing private borrowers at a further disadvantage to SOEs. Moreover, the Government’s recent attempts to ‘clamp down’ an excessive debt have disproportionately affected the shadow banking sector. In other words, while China was in the process of piling on debt[14]…

…It was disproportionately being allocated to SOEs. But now that China is attempting to reign in its debt, the private sector has experienced the monetary tightening more strongly.[15]

In addition, SOE advantages over the private sector are not based purely on easier access to cheap credit. There are also a range of regulatory barriers that affect private sector businesses to a greater extent than SOEs. For example, private companies must obtain licenses to operate in certain sectors, while SOEs do not need to do so. Some industries are completely closed off to private sector competition – consistent with the above hypothesis that SOEs operate inefficiently because they are relatively more sheltered from market discipline, the SOEs facing no private sector competition whatsoever have an even lower return on assets than those operating in markets that also contain private sector competitors.

In summary, China’s past decade or so has been characterised by a state-backed process of allocating more and more resources to SOEs at the expense of the private sector, in spite of the private sector’s superior efficiency.

As a final point, it is worth noting that the uncompetitive advantage held by SOEs is also held to a lesser extent by previously state-owned companies that have been privatised – privatised former SOEs enjoy access to lower interest rates than always-private firms, in spite of poorer returns on assets, albeit to a lesser extent than SOEs proper[16]:

This indicates that these previously state-owned companies continue to benefit to some degree from their links to Government, indicating that the (highly conspicuous) hand of the state is active not only in advantaging SOEs relative to private firms, but also in advantaging private firms with strong Government connections at the expense of those without such connections.

The expanding role of the state in the economy has dragged down growth

As already discussed, SOEs have a lower return on assets than private firms, indicating lower efficiency. Similarly, evidence from the industrial sector confirms the view that SOEs tend to poorly manage the financial resources available to them. For example, China energy use dropped from 2011 – 2017, but its energy SOEs continued investing in additional capacity, and their capacity expanded massively. This shows that they don’t care about operating efficiently, they just want to be able to justify extensive borrowing.

The point is that the more of the countries resources that get utilised by these firms, the more inefficiently the entire economy will operate. Lardy estimates that big improvements could be achieved if SOEs utilised their resources as efficiently as the private sector.

Future Prospects

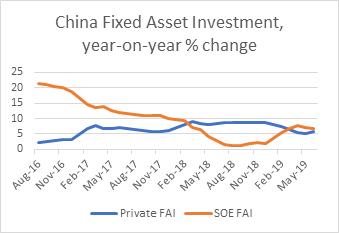

If China continues reversing its earlier pro-market reforms and allocating progressively more resources to SOEs, its growth will continue slowing. But this outcome is not a foregone conclusion. For example, data on fixed asset investment year-on-year growth indicate that the growth advantage of SOEs in this area has been falling since August 2016, and there was even a period in 2018 when private sector FAI grew faster than SOE FAI:

And the government appears to recognise the dangers of stifling China’s private sector – in November 2018, it announced plans to ensure that at least 50% of bank loans would be issued to the private sector within 3 years. Although this would still mean that the private sector (which accounts for 60% of GDP) would be under-represented among borrowers, it would nevertheless be a good start given that private companies currently owe only 25% of corporate debt.[17] Whether the government follows through on this commitment is a different matter, – official policy and stated attitudes towards the private sector have zig-zagged over the past few years with little consistency.

Moreover, president Xi appears to believe that the only way to preserve the power of the communist party is to entrench its involvement in the nation’s economy. While he maintains this view, it is unlikely that little more than soundbites and insubstantial pro-market policies will be introduced to curtail the state’s role in the economy.

One might be tempted to take away the following rosy conclusion from all of this: given that economic freedom and private sector autonomy are strongly related to civil and democratic freedoms[18], it emerges that China faces a choice between two options:

- It can either continue to suppress private sector growth, in which case it will become less of an economic (and thus military or geopolitical) threat to the West, OR

- It can reverse its suppression of private sector growth, in which case its economy will grow but its society will also liberalise and democratise, meaning that it will still not be a threat to the West (because liberal democracies very, very rarely make war with each other[19]).

According to this line of reasoning, either way, China will not pose a threat to the West in the long term.

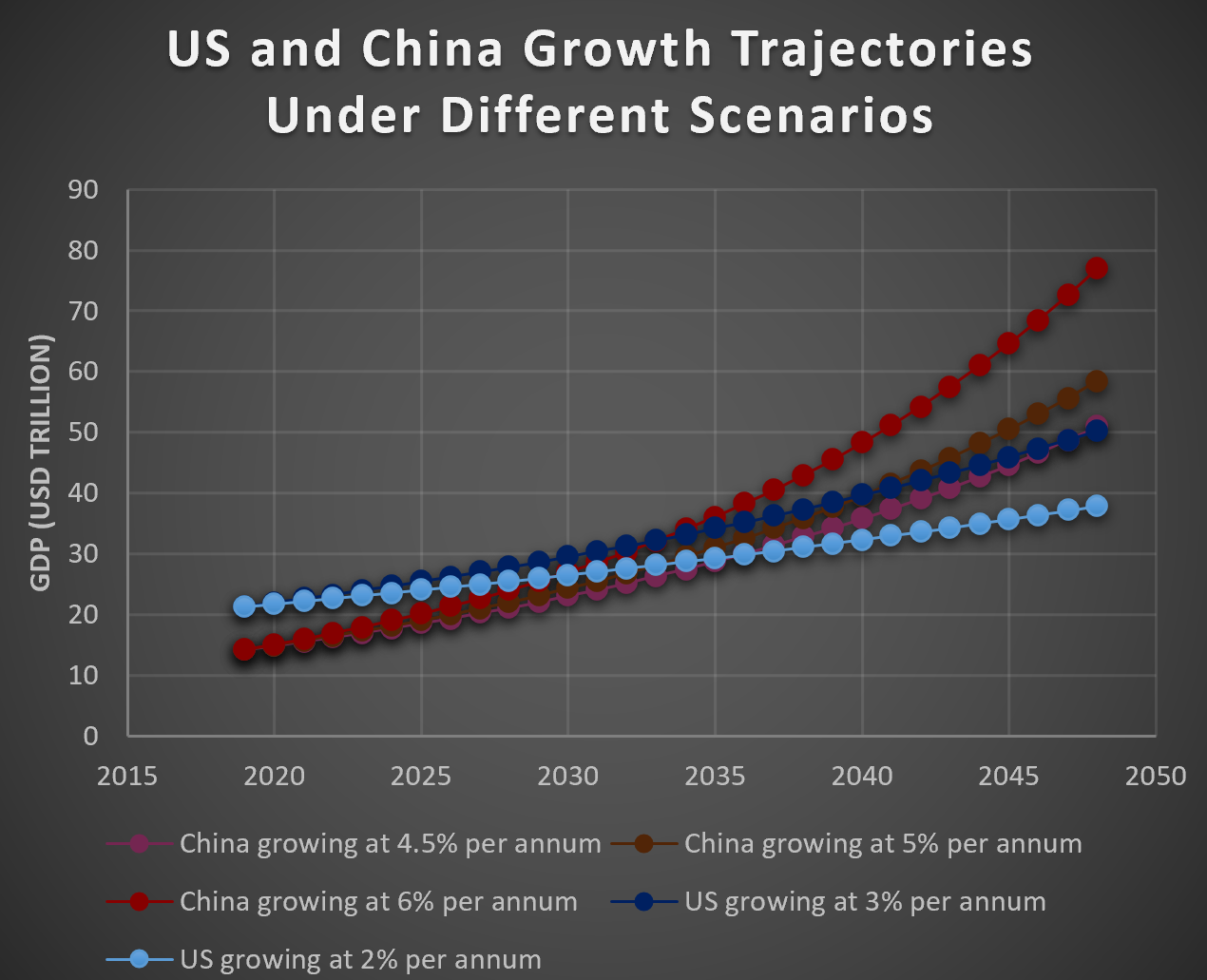

Ignoring the assumption that economic freedom necessarily leads to political/democratic freedom, which is already questionable (see the counterexample of Singapore), I believe that such a conclusion would be premature. Even if China continues down the path of increasing SOE involvement in the economy, we should not get complacent about the size of its impact on the global economy in the decades to come. This is because China’s population is so stupendously large that it only needs to attain a fraction of the GDP per capita of, say, the United States in order to achieve an equivalent share of global output. Indeed, China’s current GDP in 2018 was less than $10,000, whereas the US GDP per capita was almost $55,000; but overall GDP was $14.2 trillion for China and $21.3 trillion for the US. In other words, China’s overall GDP is close to that of the US (in fact, China has the second largest economy in the world) by virtue of its large population (which also brings down its GDP per capita).

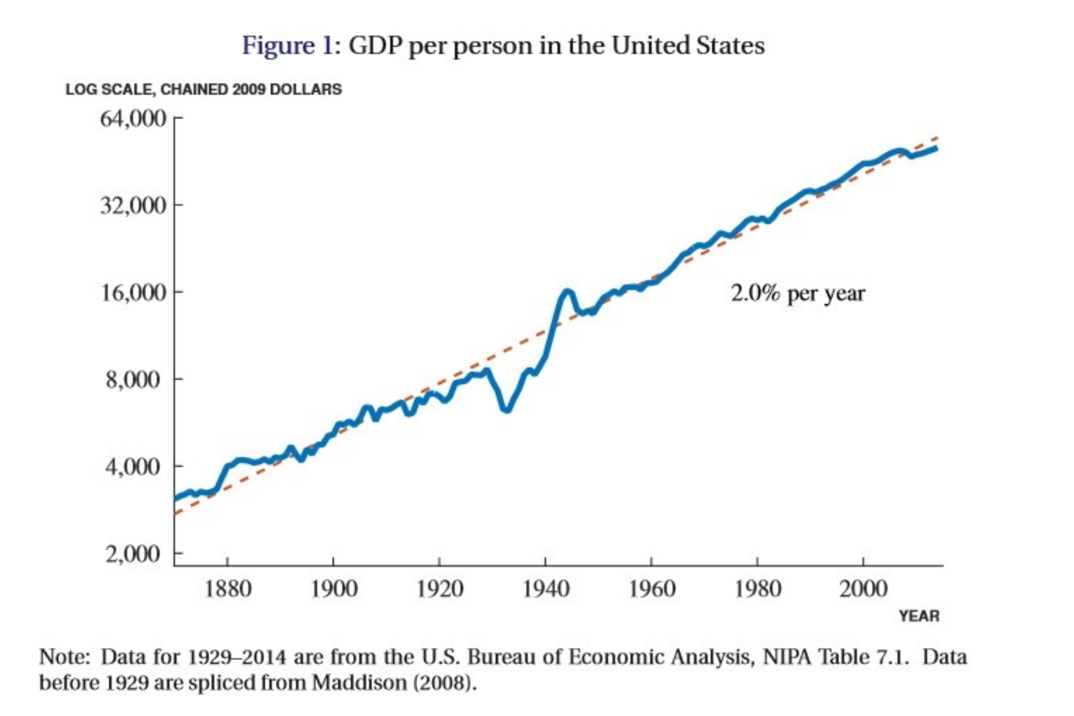

This means that China does not need to operate a super-efficient, excellently managed economy in order to dominate global output in the coming decades. If it does a mediocre, sub-par job of running its economy, it will still be almost inevitable that its overall GDP will far surpass that of the United States within a few decades. Even very pessimistic projections of China’s GDP growth – including those that assume an expanding role of the state – predict that it will grow at an average annualised rate of around 4.5% per year into the foreseeable future. Given that the US has achieved an average 2% annualised growth rate for GDP per capita going back to mid-19th century…

…China’s 4.5% would be sufficient to surpass the US fairly soon:

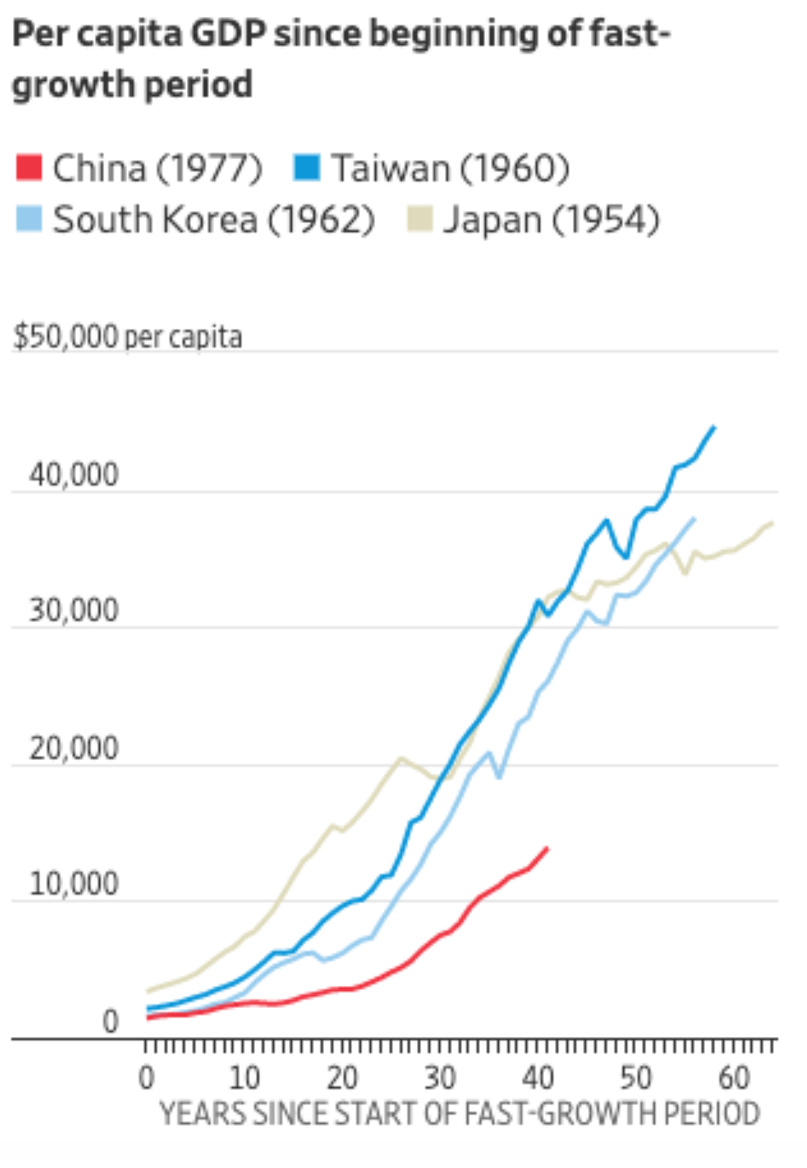

And considering China’s stage of economic development relative to other countries that have previously experienced super-rapid growth, the prospect of China continuing to achieve large gains in GDP per capita appears extremely likely[20]:

In other words, while the Chinese government’s economic mismanagement could have the effect of knocking a few percentage points off annual GDP growth over the long term, this will not be enough to prevent China from becoming the world’s most powerful economic actor over the coming decades. China’s population is so large that it has the capacity to vastly outgrow its rivals even with a very low GDP per capita (i.e. a relatively inefficient economy in terms of output per person).

And this point is reinforced by the fact that, while the heavy hand of the Chinese state is clearly posing problems for its economy, the private sector clearly continues to play a major role. Yes, SOE fixed asset investment has grown faster than private FAI over the past five years or so, but it remains the case that private enterprises still pour much more money into FAI than SOEs[21] (though of course this gap has been closing). And private sector FAI year-on-year growth has reached impressive levels (consistently above 5% since 2017) in spite of SOE crowding out. And yes, SOEs receive disproportionate access to cheap credit, but the market still plays some role in allocating resources in China – private sector companies can at least partially make up for their financing difficulties through higher profits.

Thus, the problems caused by an overly interventionist state

notwithstanding, China still appears capable of achieving a basic level of

private sector autonomy within its economy while still exerting sufficient

influence through SOEs to entrench the state’s control over people’s lives.

This will enable China to continue its fairly strong growth (even though it

would perform better if it were to continue with its past free-market reforms)

and this ‘fairly strong growth’, while likely pitiful compared to the past few

decades of ~10% per annum, will nevertheless be sufficient to create a China

that is both suppressive enough and powerful enough that it poses a major

threat to the Western world order.

[1] https://www.ft.com/content/4ad165b0-be38-11e9-b350-db00d509634e

[2] https://www.ft.com/content/825bc35e-a849-11e9-984c-fac8325aaa04

[3] https://tradingeconomics.com/china/current-account-to-gdp

[4] http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-03/06/c_137020127.htm

[5] http://markhumphrys.com/capitalism.html

[6] https://seekingalpha.com/article/2509055-china-is-still-reforming

[7] https://www.piie.com/blogs/china-economic-watch/chinas-private-firms-continue-struggle-part-ii

[8] https://cloudfront.ualberta.ca/-/media/china/media-gallery/research/policy-papers/soepaper1-2018.pdf

[9] https://www.ft.com/content/7bb41e07-570d-376b-9d23-58101403e346

[10] https://www.ft.com/content/56771148-1d1c-11e9-b126-46fc3ad87c65

[11] https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/People%27s-Republic-of-China.-Cheng/16dc88aa9e85106f2029bbcda596d7996c44df32/figure/13

[12] https://www.vanguard.com.hk/portal/articles/research/markets-economy/chinas-path-to-higher-productivity.htm

[13] See Lardy (2019); https://www.piie.com/bookstore/state-strikes-back-end-economic-reform-china

[14] https://www.ft.com/content/0c7ecae2-8cfb-11e8-bb8f-a6a2f7bca546

[15] https://www.ft.com/content/56771148-1d1c-11e9-b126-46fc3ad87c65

[16] https://voxeu.org/article/reform-chinese-state-owned-enterprises-penumbra-state

[17] https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/China-tells-banks-to-double-private-sector-corporate-loans

[18] https://www.heritage.org/trade/report/2018-index-economic-freedom-freedom-trade-key-prosperity

[19] https://www.jstor.org/stable/20097449?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

[20] https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-state-driven-growth-model-is-running-out-of-gas-11563372006?ns=prod/accounts-wsj